Monty Graham has spent most of his life guided by two passions: the ocean and time. As a child in Danville, Kentucky—over 400 miles from the nearest coast—he remembers going out with his mother to search for crinoids and other marine fossils, from Kentucky’s deep past as a former ocean. He devoted his career to studying jellyfish, one of the oldest groups of animals on Earth.

But for Graham, the future holds just as strong a pull as the past. He studied jellyfish blooms in part because they’re harbingers of larger changes in the ocean. And in 2010, when the Deepwater Horizon oil spill wreaked havoc on communities on land and at sea, he led multi-organizational efforts to understand its larger ripples on marine life.

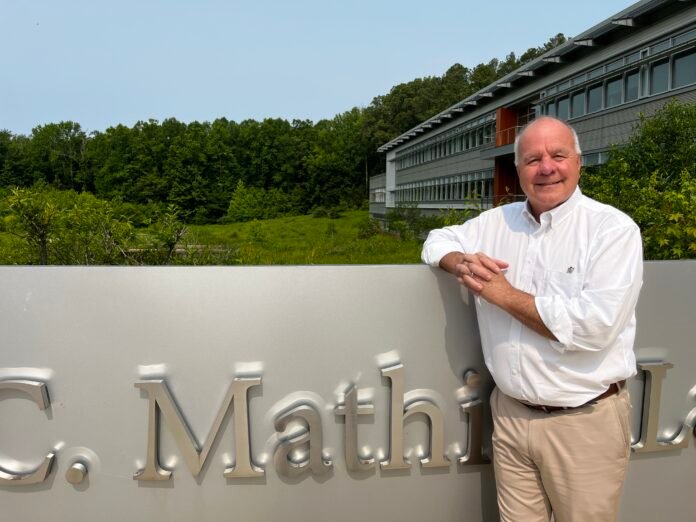

All those experiences shaped his mind for the role he took on this June: the new director of the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center (SERC).

“During and after the oil spill in the Gulf, we relied heavily on the rich historical data to guide us on impacts, recovery and restoration,” Graham said. “I am an advocate for long-term datasets like those at the center of much of SERC’s science activities.”

SERC is doing, in Graham’s words, “the kind of science only the Smithsonian can do.” It has long-term datasets stretching decades into the past, as well as projects that fast forward to the future.

In the coming months, Graham aims to bring SERC science to the larger world—by showing how its vast stores of knowledge are transforming people’s lives across ecosystems, across industries and across time.

The Biologist

William “Monty” Graham (the nickname comes from his middle name, Montrose) spent his early childhood in New England. A trip to the Boston Aquarium, now called the New England Aquarium, first sparked his interest in marine biology. He flirted briefly with seaweed research as an undergrad. But jellyfish would ultimately prove his most enduring scientific relationship. During a post-graduate internship, his mentor Alan Shanks asked him to find out why schools of cannonball jellies were all swimming in the same direction, and Graham was hooked.

“We’ve got critters that are 500-plus million years old, don’t have a brain, and they’re showing all this crazy behavior,” Graham remembered thinking.

In 1995, Graham arrived at the Dauphin Island Sea Lab in Alabama. There, he began working with the jellyfish that would later bear his name. Graham brought dozens of his students to the sea lab, first at the University of South Alabama and later at the University of Southern Mississippi. His teams made groundbreaking discoveries on jellyfish behavior and how massive jellyfish blooms can impact people and the environment.

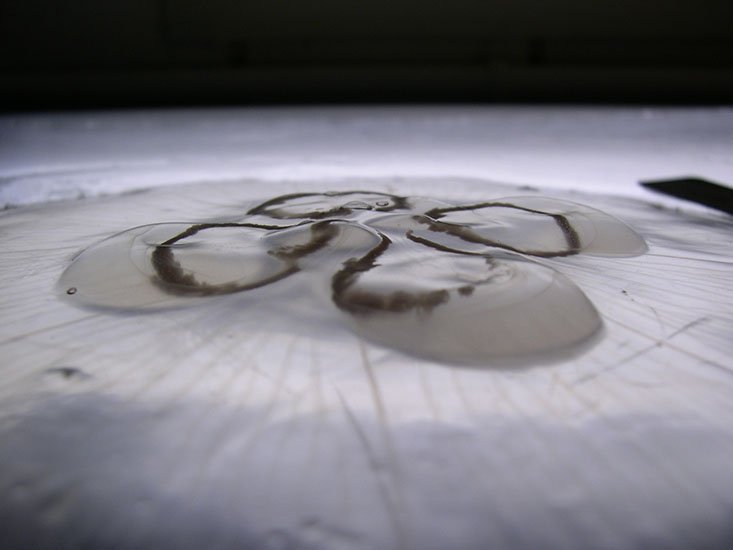

For over two decades, Graham and his students studied a moon jellyfish known only as “Aurelia sp. 2,” or later, “Aurelia c.f. sp. 2.” That’s scientific lingo for when scientists suspect a group of organisms might be its own species, but they lack solid confirmation.

In 2021 that confirmation finally came through, in part thanks to one of Graham’s former students, Luciano Chiaverano. A genetic analysis Chiaverano co-authored identified 28 species of moon jellyfish—far more than anyone had predicted. Aurelia sp. 2 was in fact a new species not found anywhere else. And it could at last receive a proper name. Chiaverano thought Graham deserved the tribute, so he called his former mentor on the phone.

“He gave me a choice,” Graham said. “He said, conventionally, it would be your last name. But what do you think about Aurelia montyi? Do you want Aurelia grahamii or Aurelia montyi? And I said, I like ‘montyi.’”

(Coincidentally, the same study named another moon jellyfish species Aurelia smithsoniana, after the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute in Panama. Sometimes science is a small world.)

The Bridge Builder

Always looking for deeper connections, Graham spent much of his later career building bridges. As director of the Florida Institute of Oceanography (FIO)—the last position he held before coming to the Smithsonian—he led a coalition of roughly 20 universities, state agencies and other nonprofits dedicated to marine science.

One of the most rewarding bridges he helped create was the Peerside Program, he said. Peerside offers students with limited opportunities hands-on training in ocean science aboard research vessels. It’s still running out of FIO today.

After doing so much work to advance science regionally, joining the Smithsonian offered a chance to shape science globally. Graham is preparing to create more bridges at SERC. This time, he’s aiming to connect people with all the ways science is improving and even saving lives.

Environmental science is “the business of keeping losses from happening,” according to Graham. That’s a message that’s easy to miss.

“People never see the loss,” he said. “And if they never see the loss because a resource was managed right, or because we had predictability in a storm, or people didn’t get sick because of pollutants in waters, we’ve done our job.”

Since its creation in 1965, SERC has specialized in connections: between the land and the sea, between predators and prey, and between people and nature. Graham aims to emphasize a fourth connection: between the past and the future. For example, Graham said, how past humans responded to changes like rapid sea level rise could offer clues for society today.

It’s part of what Graham refers to as “The Long Now”—a phrase first coined by British songwriter Brian Eno, which Graham mentioned in his first Director’s Letter. “The Long Now” represents the idea that people today are products of their past and create ripples that will last generations into the future. It’s a concept especially relevant to environmental science and how society evolves with the natural world.

“The Smithsonian is an institution of the ‘Long Now,’” Graham said. “It’s all about the past and it’s all about the future, and we just happen to be the caretakers.”

Read Monty Graham’s first Director’s Letter from fall 2025: The Smithsonian’s Long Now